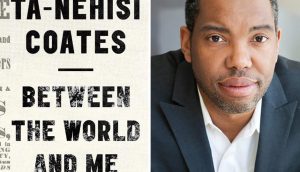

A couple of years ago a small group of us at RCWMS took up Ta-Nehisi Coates’ challenge to followers of his blog at The Atlantic to read and discuss Michelle Alexander’s magisterial book on mass incarceration, The New Jim Crow. (You can read a brief review on our Words and Spirit blog: wordsandspirit.tumblr.com) The discussions about the book made us want to further explore how racism and white supremacy have profoundly undermined our ability to  imagine and move towards the world we want to create. For our second book we took on Coates’ brilliant and moving letter to his son, Between the World and Me. In this book Coates eloquently describes what it is like to live in America, in Baltimore particularly, in a Black body. He insists on the centrality of embodiment to the Black experience. He also introduces us to the notion of people who “believe themselves to be white,” a phrase that he borrowed from James Baldwin. Throughout our subsequent reading we have continued to explore the implications of this provocative phrase.

imagine and move towards the world we want to create. For our second book we took on Coates’ brilliant and moving letter to his son, Between the World and Me. In this book Coates eloquently describes what it is like to live in America, in Baltimore particularly, in a Black body. He insists on the centrality of embodiment to the Black experience. He also introduces us to the notion of people who “believe themselves to be white,” a phrase that he borrowed from James Baldwin. Throughout our subsequent reading we have continued to explore the implications of this provocative phrase.

Our conversations about these two books helped to deepen our understanding of these vital  issues, but also showed us how much more we have to learn. So we invited a few more people to join us and kept going. During this past winter and early spring we read three books that focus primarily on the Black experience: Citizen, by Claudia Rankine (also with a Words and Spirit review); Americanah, by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie; and Just Mercy, by Bryan Stevenson.

issues, but also showed us how much more we have to learn. So we invited a few more people to join us and kept going. During this past winter and early spring we read three books that focus primarily on the Black experience: Citizen, by Claudia Rankine (also with a Words and Spirit review); Americanah, by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie; and Just Mercy, by Bryan Stevenson.

Rankine, a poet, presents essays and prose poems that are part memoir and part social commentary, including an eye-opening essay on the gender and racially-tinged politics around Serena Williams. The words are complemented by stunning artwork; the whole book is a work of art.

In Americanah we follow the journey of Ifemelu, a young woman who travels to America from her home in Nigeria to attend college. Through Ifemelu, and Adichie’s beautiful prose, we get an intimate portrait of what it is like to encounter America’s racial complexity as an African immigrant. And via Ifemelu’s blog posts we get a pointed commentary on race in America.

The third book, Just Mercy, documents the recent history of the death penalty and the work of the Equal Justice Initiative that Stevenson founded in Montgomery, Alabama. In the book Stevenson intersperses chapters tracing the case of falsely-accused death row inmate Walter McMillian with other chapters outlining the larger politics and issues surrounding the death penalty.

In the past couple of months we have been focusing on whiteness. We started with Jennifer Harvey’s Dear White Christians, a book that makes a compelling argument that churches, and by extension other institutions, make a fatal error when they focus their anti-racism efforts on the laudable goal of reconciliation. Harvey argues that before there can be any hope of reconciliation, we must do the slow and arduous work of confronting the white supremacy that permeates our society. She calls for repentance and a “reparations paradigm,” building on the work of the Black Power movement and its challenge to white-dominated churches.

Most recently we discussed Dog Whistle Politics by Ian Haney López, which traces the use of thinly veiled racist language in presidential campaigns since the days of George Wallace and Barry Goldwater. He makes the compelling case that dog whistling (using racially charged images such as “welfare queens,” and racially coded language such as the war on drugs or being “tough on crime”) has made possible the unraveling of middle-class prosperity through the deliberate actions of those who would shape the world to their own advantage. Not to mention its devastating impact on people of color.

Our conversations have opened our eyes, taught us many things, and helped us to understand how much more we have to learn. After a summer-long hiatus, we will resume in the fall.

Leave a Reply