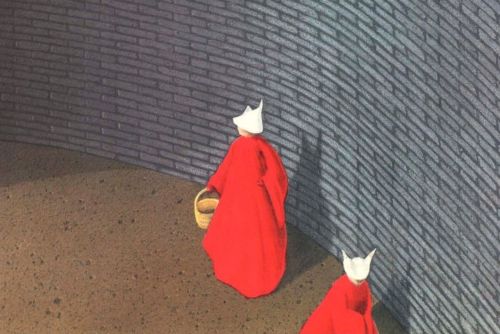

I recently found a used copy of The Handmaid’s Tale at a local library book sale. In preparation for Hulu’s television adaptation I decided it was finally time to fill in this gap in my reading life, since I generally avoid watching screen adaptations of books I haven’t read. The timing was…well, not quite good, but certainly appropriate. For one thing, because of the Hulu series, there’s a lot of buzz around the book right now, which means a lot of feminist writers I admire are revisiting it. Margaret Atwood herself wrote a fantastic piece for The New York Times, and Rebecca Traister, one of my current favorite writers, also wrote a striking piece for New York Magazine. And finally, Jessica Valenti, writing for The Guardian, summed up my own experience reading the book for the first time in this era, noting that rather than “timely” The Handmaid’s Tale is timeless. Long before Margaret Atwood wrote it, and no doubt far, far into our future, the world of Gilead was and remains relevant to the actual world in which we live. Atwood herself describes in the Times article how she refused to include anything in the world she built that had not actually occurred in reality, somewhere, sometime, and that is why the book is so chilling. On one hand, you might read it and think, is this our possible future? And on the other, you know that, if not all at once, it has in fact been our past and is in certain ways our present. Our future? It remains to be seen.

The main strength of the screen adaptation lies in its ability to provoke a guttural sense of this timelessness. As I have watched, I alternate between fascination with the producers’ artistic choices and deep emotional resonance. “My God,” I have thought during nearly every episode, “this is how much men hate women, how afraid men are.” And: “This is how quickly things change.” This is what it looks like when men make rules for women’s “protection.” This is how misogyny becomes internalized, how well-meaning men are complicit, how reluctant women go silent in order to survive.

People ask me if I “like” the Hulu series, given that I am often picky about adaptations. I cannot say that I like it, but I can say that I recommend it. I can say that it is brilliant, that it is faithful to the book in the ways that matter, and that it adapts in ways that are necessary when translating text to screen. I can tell you it is the most important thing I’ve watched on television in recent memory. I can tell you it is not entertaining, but that it is moving in all the ways the best television and films are. I can tell you that Margaret Atwood is a gift, and her brilliance shines through in scene after disturbing scene.

I can tell you too, that it scares me, because while I watch it and think, “this is a warning,” some watch it and think, “you’re being melodramatic, this could never happen.”

In the US, for many women, this is not far off from our very real past, a past that seems to be looming large in the rear view mirror just as some of us thought we were leaving it behind. Read Rebecca Traister on the slow erosion of abortion rights. Read about women’s access to reproductive healthcare in general. Just read, anything, everything, about being a woman in the world, and the lengths to which men will go in order to contain us, to control our bodies. Atwood’s Gilead is fictional, but the best fiction is also true.

One of the most disturbing scenes for me from both the book and the television series is when the women gather in the Red Center, and shame a woman who was gang raped. It is not disturbing for its “this could happen here” quality, but because it does happen here, in mainstream news outlets as well as right wing talk radio – on the national stage as well as in the smaller, secret power moves of men who gaslight the women they’ve hurt. “Her fault,” they whisper. “Her fault,” they scream. Offred watches in horror as her peers jeer and point, until she joins in.

Present day politicians hold to ideologies that are remarkably consistent with Gilead’s forced birth practices. Abortion is legal, albeit difficult to obtain in many cities and states, and under threat daily on both state and federal levels (again, see Traister’s article on the gradual chipping away of these rights). And even if you leave abortion out of it, there are a million other ways women’s bodily autonomy is under threat every day. After all, this is as much about women being able to choose to carry – and raise – children as it is about choosing not to, an issue that cuts to the heart of gender, race, and class. As our president’s “healthcare” plan threatens to make so many aspects of women’s healthcare prohibitively expensive, it’s clear that while this administration wants to mandate reproduction for some – namely upper class white women – they want to make it impossible for others – poor people and women of color – to carry and care for their children. Women, both those who do and those who do not want children, will die because of these kinds of policies. There’s no fiction in that.

Leave a Reply